Children who experience violence, neglect, hunger, housing insecurity, abuse and other serious trauma in their early years may grow up to be quick to anger, impulsive, jumpy and hyper-vigilant, depressed, suffer nightmares and insomnia, have poor working memory and show other symptoms similar to war vets diagnosed with PTSD. Their fight-or-flight stress response has become hyper-sensitive and easily triggered, and their brains always on alert for threat. These behavior and learning difficulties are actually a result of changes in the wiring of their brains, not just "bad behavior."

This “always-on” stress response can be protective and adaptive where danger is prevalent. But it becomes maladaptive and health harming in places like school classrooms. What’s more, high doses of adversity don’t just affect behaviors, they can also alter the immune system, hormone secretion even change how genes are expressed. The result is increased risk for heart disease and other chronic diseases that don’t show up until years later.

There is an important difference, however, between children with PTSD-like symptoms and returning combat vets. First, they are children. Their brains are still developing and particularly vulnerable. Second, for many of these children, there is no “post.” They may be exposed to a prolonged stream of adversities from birth—chronic noise, crowded and unstable homes, family fears about money and job prospects, domestic turmoil and violence, incarcerated parents, community violence and shootings, substance abuse, neglect and maltreatment. When children experience this continuous and chronic activation of the stress response, psychologists call it “complex trauma” (some call it chronic trauma).

Burdened by poverty and neighborhoods depleted of resources, daily gunshots and the exclusion and stigma of racism, many teens are unable to imagine a safe, successful future for themselves. Researchers estimate that some poor, inner city neighborhoods have post-traumatic stress syndrome rates approaching 40%.

Children with complex trauma, like combat vets, have the capacity to heal. The brain remains plastic. Adversity is not destiny. Trauma is treatable. The conditions which produce it are preventable. But the healing begins by treating these children not as “bad kids” but as injured kids, children who have faced adversities others haven’t. The road to healing begins by asking not “What’s wrong with you/us/me?” but “What happened to you/us/me?” And that’s exactly what many “trauma-informed” doctors, schools, social service agencies, even some police forces, are beginning to do.

TAKE-AWAY

Some children in America who are growing up in the face of poverty and violence develop symptoms that are remarkably similar to PTSD-afflicted soldiers. The big difference is these children never leave the combat zone.

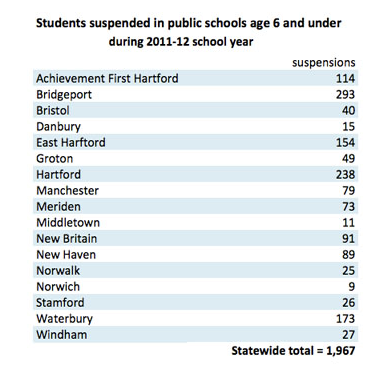

In 2012, in Connecticut alone, almost 2,000 children 6 years and under—overwhelmingly black and Latino—were suspended from kindergarten and preschool.

In 2012, in Connecticut alone, almost 2,000 children 6 years and under—overwhelmingly black and Latino—were suspended from kindergarten and preschool.